Why the greats aren't always the best motivation

When the moon is an obviously unrealistic target, perhaps a more attainable goal will provide a better push?

There have been two moments in my life where seeing somebody else be so floresently exceptional at something it damn near made me quit pursuing said thing as a personal goal.

The first was when I was around 20, maybe just after junior hockey, when I was playing summer hockey back in Kelowna trying to prepare for an upcoming season. I had worked my way into The Summer Skate in town, which at the time was run by Kelowna Rockets star (and then-NHL player) Brett MacLean, which I “worked my way into” thanks mostly to a fortunate dating connection and not my playing ability.

The Skate was predictable, in that the best players never touched the ice until August, focusing their efforts on the gym and taking some much needed rest from the daily grind after a long season. (That crew occasionally included guys like Duncan Keith, Shea Weber, and Scott Hannan; the quality of talent there would be tough to overstate.) Fringe AHL/NHL guys were usually back on the rink in July, and I was among a crew of players who skated basically all summer, particularly during my college years when the season would be over by April at the very latest.

The one outlier to these rules was Dany Heatley, in that he was among the elite players (obviously), but at times he would come out and skate earlier in the summer, mostly because he found it a more enjoyable form of cardio to take on than say, running or pounding a stationary bike.

And so, for years I was privileged to intermittently skate with him and his brother Mark. But Heatley was out there with, again, not the A squad of summer skaters, and at that time he had already banked a 41-goal NHL season, building up to 50. To say the talent disparity was great doesn’t do it justice.

The first time I saw Heatley shoot the puck - at a time where I was on the ice with him, and had the proper context for the weight of his shot - was the first time I started to thinking about baking or carpentry or how much I could get if I sold my gear. Like, I was grinding my way up the ladder at that time. I had barely made my Junior A team at 18. I worked hard to matter there, and by age 20, I had earned a D1 scholarship by the skin of my teeth.

Heatley was a different species than me.

I was steadily improving, but there was no fucking way, not an ice rinks chance in hell that I could ever, ever get anywhere near as good as what he was then. It wasn’t just his shot, he was a massive, massive guy (checked in at 6’4”, 225), and he could skate way better than anyone gives him credit for. Young Heatley could really move. I felt like a kid on the ice with their Dad, there was just nothing I could’ve done to have stopped him from doing whatever he wanted to do out there.

Then, for just a few moments, I found it discouraging. I had seen my ceiling clear as day.

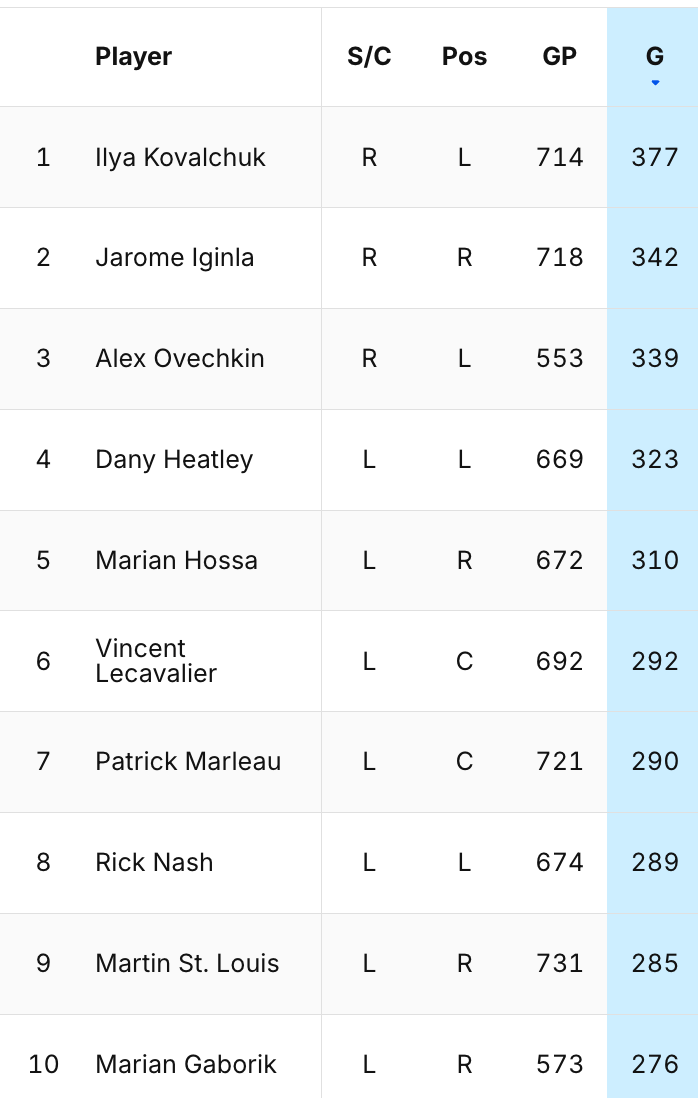

For further context, this is over a ten-year NHL span from 2002-03 to 2001-12:

These days, I recognize that prime Dany Heatley he was one of the best goal scorers of the 21st century (he literally won the Rocket Richard Trophy), and I didn’t have to get anywhere close to as good as him to make the NHL. Like, not even close.

They tell you to “shoot for the moon, and you’ll land among the stars,” but surely that unrealistic thinking is counterproductive. I wasn’t dumb. I couldn’t have been on the ice at peak motivation, firing buckets of pucks at the corners hoping to catch Dany Heatley. I’d have known that was futile. I think it would’ve been more motivating to recognize that he was the outlier, and that if I worked hard enough, I was more than capable of getting to a level that could’ve played in the same games that he did. It would’ve been more motivating to look at some of the fringe guys and think “OK, I can get there,” and use that when I needed an extra boost of motivation. You’re more likely to keep working when the goal’s in sight.

The other moment I had came after my playing days, when I took on the writing side of the business. Pre-sobriety I didn’t have the brain power to hold a coherent narrative in my head, so I didn’t read much, if at all. Post-sobriety, it became an obsession, and I wanted to go back and read a whole bunch of classics I felt I had missed.

I’m not sure you’d call it a “classic,” but I wanted to read some Cormac McCarthy, and a friend pointed me to Blood Meridian, which to this day is the most violent piece of entertainment I’ve ever consumed, holy shit. I was not prepared for that. But it’s a staggering work, because on top of the violence is layered this most beautiful writing, which almost serves as a soothing blue cheese dressing on the incinerator sauce wings he otherwise serves up.

I remember reading the below passage before just looking up at the roof, exhaling deeply, staring again at the page, and muttering “fuck.” I was just never gonna get there.

“…and the sun when it rose caught the moon in the west so that they lay opposed to each other across the earth, the sun whitehot and the moon a pale replica, as if they were the ends of a common bore beyond whose terminals burned worlds past all reckoning.”

Like, goddammit.

No amount of “reps” were ever going to get me there. I could hammer away at this blog for rest of my life and never write a sentence like that. And, in some ways, in that first moment, it was depressing.

But McCarthy isn’t just the Dany Heatley of writing - though it occurs to me that’s a hilarious piece of slander to drop on someone at some point - McCarthy was often cited as the “greatest living American writer” until he passed just a couple years back. He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. That’s an insanely high bar. So he’s like … the best guy, or at least among the greatest few we’ve got.

The point here is, the older I get, the more I realize the value in the pride of being just plain old reliably good. And this mentality, this acceptance that really good is still really good even if it isn’t exceptional greatness, it applies even more so when it comes to the arts, as they’re so much of it is subjective. You can’t argue that a bottom-six NHL player was “better” than prime Dany Heatley was, because it would be just flat out wrong. But you can sure enjoy a certain kind of music more than someone else, or a style of painting, or a pattern of writing.

In fact, I’m am 100% certain there are at least a few strange people who’d prefer reading my writing style - which is really just “dressing room banter with a thesaurus” - to McCarthys. I mean hell, he barely uses punctuation and his sentences run like Andre De Grasse.

Aspirations differ, and if you’re young and super ambitious it certainly makes the most sense to shoot for the pale replica, for bore hole that is the moon. But at some point, as a grown up, you’re searching for other things - a good income, steady employment, the respect of your peers and more. Very few of us are worried about vying for our field’s Mount Rushmore.

And so to me, once you remove the outliers from the pack, if you can recognize that you’re good at something, and in the upper percentile of those who do it, it’s such motivation to grind a little harder. Maybe I won’t be in the 99th percentile, but if I’m in the 92nd, how much more valued and respected would I be if I could get to the 93rd? What about the 94th?

At those levels, the dollars and acknowledgement and personal pride that you can take increase exponentially, and you’re running out of people who are above you, even if you’ll never catch a few.

Life is hard enough, and we’re smart people who know roughly where we sit, and where we can get to. So look at the moon, sure, admire the moon, respect the moon. But for most of us, we’re not destined to change the tides, and accepting that is a relief that holds neither shame nor frustration.